Sanism and the Psychologisation of Physical Illness

People with myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME) usually react negatively to the suggestion that our illness is psychosomatic. Psychologisers often retort that our reaction originates in and reveals negative attitudes towards mental illness.

Before examining this rhetorical device, we need to be clear on why people with ME actually resist the psychologisation of our illness. As I explained in a previous blog post, state and medical institutions together with insurance companies have controversialised ME: they have buried the unequivocal evidence that ME is a physical illness in an effort to avoid funding research into treatments, medical care, and social support for the millions of people disabled by ME. Their main strategy has been to fund, reward, and amplify the fraudulent research of a handful of psychiatrists arguing that ME is nothing but “false illness beliefs” held as a result of social influence in order to reap the supposed benefits of the “sick role”. The resulting widespread narrative that ME is a mental illness has served as an excuse not to fund the desperately needed further research into the immunological, metabolic, neurological, and vascular aspects of our illness that would lead to effective treatments. This is the first reason for our rejection of the psychologisation of our disease: because we recognise it for the tool of controversialisation that it is.

But psychologisation doesn’t just impact which research programmes get funded, it also impacts how sick people are treated in the clinic. While there are no approved treatments for ME, several treatment options that target the metabolic, immunological, vascular, and neurological aspects of the illness exist and are prescribed off-label by knowledgable clinicians. Beyond these, there are numerous treatment options for the symptoms and comorbidities of ME, especially MCAS and POTS. Although none of these treatments constitue a cure, they can substantially improve people’s quality of life. The psychologisation of our illness serves as a justification to deny us these treatments. If ME is ultimately a mental illness, and not a physical one with immunological, metabolic, vascular, and neurological aspects, there is no reason to prescribe drugs that target these bodily systems.

Instead, there is a reason to target the alleged mental disorder (the “false illness beliefs” held for the “benefits of the sick role” and encouraged by “social contagion”) at the root of the illness. Thus in lieu of the biomedical treatments we need, we are encouraged (indeed often coerced) by clinicians to cut ties with our communities, which are sources not only of support but also, as I explained in a previous blog post, of scientific knowledge; and to undergo cognitive behavioural therapy designed to train us to dismiss and ignore our own physical symptoms, and graded exercise therapy designed to force us into a level of activity sufficient for participation in the workforce. But since the cardinal feature of ME is that it gets worse with activity (this is called post-exertional malaise or PEM), training people to ignore their symptoms and increase their activity levels on account of the supposedly mental nature of the illness has catastrophically harmed countless people: innumerable people have permanently lost even more function, many to the point of becoming bedbound, and some have died.

And psychologisation doesn’t just happen with ME; other controversialised illnesses are massively psychologised. People with POTS, a disease of the autonomic nervous system which, among other things, makes it extremely difficult to be in an upright position, are told our disease amounts to a “fear of standing”. People with MCAS, a disease of the immune system that causes sometimes extreme reactions to numerous foods (as well as chemicals, medications, and even environnemental factors like temperature and air pressure changes) are often diagnosed with eating disorders. Etc.

Now, it is important to understand that controversialised illnesses like ME, POTS, and MCAS are not special cases, qualitatively different from legitimised ones. Instead, the treatment we receive from medical institutions is the standard treatment everyone receives, taken to the extreme. Thus legitimised though minimised physical illnesses, such as endometriosis and migraines, are also routinely psychologised. Even people with arch-legitimised illnesses like cancer are subjected to the psychologisation of many of their symptoms. Moreover, as anyone with a physical illness will know, especially if they are targets of racism, fatphobia, classism, and cisheterosexism, it is an ordeal to get doctors to investigate physical symptoms and get a diagnosis: psychologisation is a major tool of healthcare refusal even for otherwise abled people. This phenomenon is so serious that it takes several years for autoimmune diseases, which predominantly affect women, to be diagnosed on average; and it is common for people’s diseases to progress severely, sometimes to the point where they are terminal, before doctors cease to psychologise them.

Thus it should be clear that physically ill people’s resistance to psychologisation is rooted, not in negative attitudes towards mental illness, but in negative attitudes towards the institutional neglect and abuse we suffer at the hands of psychologisers.

***

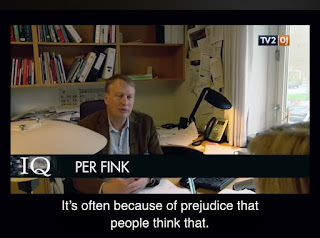

With this in mind, we can now turn our attention to the accusation of, in the words of Per Fink from the photo above, “prejudice” against mental illness that supposedly undergirds our resistance to psychologisation. If we are going to talk about the oppression that mad people suffer, we should start with their struggle as theorised and understood by them: under the term sanism. Though of course that includes attitudes and beliefs—beyond the vague “prejudice” that Per Fink invokes, the widespread beliefs that people with mental illnesses are lazy, dangerous, irrational, defective, immoral, fakers, etc.—mad people have been more interested in the material dimension of sanism: in the interpersonal violence, neglect, and abuse to which they are subjected, in their exclusion from the workforce, but most of all, in their state-engineered and state-executed oppression.

On the one hand, mad people deemed threats to public order (i.e. to bourgeois social life) are often detained in psychiatric institutions, where they are held sometimes for decades, and routinely subjected to physical and chemical restraint, seclusion, surveillance, and totalising control (over their food, schedules, activities including social ones and political ones, etc). In line with non-psychiatric incarceration, institutionalisation is horrifically racist; in the UK for instance, Black people are five times more likely to be sectioned than white people.

On the other hand, mad people are also systematically abandoned by healthcare institutions who refuse them adequate care. State-issued or state-funded mental healthcare is essentially impossible to access (in the UK, there are currently a million people on the waiting list), and when people do access it, it is often catastrophically insufficient. Quality mental healthcare is dispensed privately but is prohibitively expensive, and for certain forms of madness and neurodivergence, essentially no competent professional healthcare provision exists. Racism, classism, and cisheterosexism are rife among mental healthcare providers, alongside sanism and ableism, which makes getting adequate healthcare even less likely for those subjected to these. Finally, it is extremely hard to access disability benefits for mental illnesses, such that many mad people are forced to rely on often abusive relatives for survival, and many become homeless.

Since many people with ME (about a third, which is 50% higher than the general population and in line with other serious chronic illness) have a mental illness, sometimes predating ME, and sometimes secondary to ME, we are all too aware of the oppression of mad people. In fact, having ME makes us more likely to suffer the effects of sanism if we do have a mental illness. We are more likely to be institutionalised, and less likely to be able to access mental healthcare, due to the lack of infection control in clinical settings (infections worsen the illness so must be avoided at all costs), to rigid schedules that our fluctuating illness makes impossible to follow, to intolerance to certain medications like SSRIs, and to the fact that many of us are just too sick to be able to participate in talk therapies.

Moreover, many of the tools of sanism overlap with the tools deployed against us, regardless of whether we have an additional mental illness. Mad people and people with ME alike are viewed as malingerers, faking illness to reap the alleged benefits of the sick role and to avoid work, plagued with a motivation problem. Our suffering is systematically minimised, incorrectly blamed on our personalities, political convictions, and “lifestyles”. We are depicted as needing not accommodation and treatment, but to try harder. The fact that our illnesses are often chronic, lifelong, and have no properly effective treatments leads to similar reactions of abandonment, dehumanisation, and abuse in our interpersonal relationships. So there are many things that, in virtue of having ME, even those of us who don’t have a mental illness understand about sanism. Moreover, becoming disabled with ME often leads to exposure to disabled communities, including communities of mad people, and to anti-ableist, anti-sanist theorising; all of which contributes to the building of solidarity among differently disabled people. In light of all of this, the idea that we as a group are uniquely sanist is simply bizarre.

***

It is all the more bizarre since, unlike us, the psychiatrists who accuse us of being sanist play a large role in the production and perpetuation of sanism. After all, they are the ones institutionalising, abusing, and refusing treatment to their patients. In fact, Per Fink, shown above as claiming that the rejection of psychologisation is rooted in “prejudice” against mental illness, is well-known for having orchestrated the forced psychiatric institutionalisation of Karina Hansen, a young woman with ME, who was harmed there to such a degree there that she became too sick to speak or recognise her own father. In general, it is particularly ironic that accusations of sanism are made chiefly by professional psychologisers—Per Fink for instance is Professor of Functional Disorders and Psychosomatics.

But psychiatrists do not merely enact sanism themselves, they also shape the way mad people are viewed and treated beyond the confines of psychiatric institutions. They do so, firstly, with good old propaganda: they write countless studies, press releases, and op-eds that spread sanist ideas about madness and neurodivergence. But more importantly, they do so via material determination. This is the Marxist insight that thoughts and ideas do not exist independently of their material context (a view Marx and Engels called “idealism”), but that they are to a large extent produced by material reality. Thus the fact that mad people are much more likely to be unemployed gives rise to ideas that they are useless and lazy. The fact that they are shunned, abandoned, and abused in their interpersonal relationships gives rise to the idea that they are defective. The fact that they are institutionalised gives rise to the idea that they are dangerous, and that their autonomy is to be overridden. The fact that they are denied healthcare and benefits gives rise to the idea that they are not really ill, but faking and malingering.

It follows that what Per Fink called “prejudice” against mental illness and what we can now see is better theorised as sanist ideology is to a large extent the result of psychiatric incarceration, abuse, and abandonment. Psychiatrists do not only enact sanism directly when they undercut the autonomy of people with mental illnesses, fail to provide adequate treatment, and blame their patients’ personalities/values/politics and most of all “lifestyles” when their own treatments fail. In doing all these things, they also produce and legitimise sanist ideas according to which mad people should not be engaged with as autonomous agents, are dangers to society, are often to blame for their illnesses, are malingerers, and should be either rehabilitated into sanity or incarcerated.

This sheds some light on the significance of their psychologisation of physical illness. When they claim that we have a mental illness, psychologisers don’t mean that we suffer from e.g. depression. (Studies show that roughly 30% of people with ME have an established mental illness, a number which is higher than the general population and similar to other severe chronic illnesses.) They mean, ultimately, that we are neurotic, hysterical, confused about ourselves, lazy malingerers, who need to be forced into exercise therapies and trained out of our bad habits. They mean that our autonomy should be overridden and our knowledge dismissed. In other words, when they psychologise our physical illnesses, psychiatrists ascribe to us a terribly sanist view of mental illness, one according to which people’s agency doesn’t matter. And to ascribe such a view of mental illness to anyone is to reproduce sanist logics, that is, to reinforce the very ideology that they somehow accuse us of acting on.

Unfortunately, these ideas have spread outside of the practice of psychiatry, indeed outside of the practice of medicine, and have been taken up (usually unconsciously) by many. The psychologisation of our disease is something we are almost all subjected to by some of those around us, usually by those we depend on the most. It plays a similar role in interpersonal relationships than it does in the clinic: it serves to question the legitimacy of our illness, to express that what we have isn’t something they consider a genuine illness but a form of hysteria, and to justify their undermining of our agency and overriding of our autonomy. When we resist this, we are often met, again echoing professional psychologisers, with accusations of sanism. The very same analysis applies here: the sanist attitude is not that of pointing out that a physical disease is not a mental one, but that of invoking a covertly sanist idea of mental illness as a way to undermine our agency.

***

None of this is to say that people whose physical illnesses are psychologised do not perpetuate sanism. As I explained above, people with controversialised illnesses are more likely to be mad, more likely to suffer the effects of sanism, and more likely to be involved in anti-ableist politics; as well as being subjected to oppressive logics very similar to sanism: we are thus less likely to be sanist than the general population. But it is important to insist that many people with controversialised illnesses are sanist, especially newly disabled people who haven’t understood their situation through the lens of disability politics, and those more likely to be sanist in the first place: white, bourgeois people with an investment in respectability politics and a material interest in the oppression of mad people. Moreover, as I remarked earlier, psychologisation isn’t just used against people with controversialised illnesses; it is a feature of medical systems that is applied widely, and people with more legitimised illnesses, in virtue of their relative enfranchisement, are less likely to be ensconced in disabled communities and therefore to have developed an anti-ableist, anti-sanist consciousness.

Thus we do see people with psychologised physical illnesses suggest that, “unlike crazy people”, they are rational, legitimately sick, and have a reliable understanding of their own illness, such that they should be able to exert agency over the healthcare they receive—their expertise shouldn’t be dismissed, they shouldn’t be institutionalised, treatment shouldn’t be forced on them, etc. Here, the assertion of their own agency is interwoven with the denial of that of mad people: their rhetoric doesn’t insist on the fact that everyone should retain agency over their care, but suggests that the state’s undermining of people’s agency is sometimes legitimate, just not for them. This is a phenomenon called disavowal, whereby an oppressed group participates in the oppression of another group in order to signal alliance with the oppressor, and seek the associated benefits. In her fantastic chapter on disavowal and madness, Micha Fraser-Carroll cites Lydia X. Z. Brown:

We all learn disavowal from a young age. . . . In order to claim our own humanity, we must always do so at the expense of somebody else . . . we do it even in the most progressive and radical of movements.

By psychologising our physical illnesses, sanist psychiatrists put us in a situation where we must actively choose between disavowing mad people or standing in solidarity with them. It is imperative that we choose the latter; that our resistance to psychologisation be anti-sanist. And because psychologisation itself operates within sanist logics, rejecting it is liable to reproducing these logics. Proper resistance to the psychologisation of physical illness thus requires learning from mad people about sanism. This is something that those of us invested in a political movement for adequate healthcare would do well to pursue.

I'm a person with ME and I read this article with my partner, who is a philosophy researcher, and we loved reading it. It is so nicely structured, and has such nuanced insights, especially when it comes to infighting within the disabled community. I thought the article was so interesting, because I reckon Per Fink says what a lot of doctors think silently but do not state explicitely. It must have been what my doctors were thinking, as they kept insisting that I should try to make efforts to get better. I also hate that, prior to getting a formal diagnosis, I had to explain what ME is by constantly putting it in contrast with depression, being forced to tell them the problem wasn't "in my head", so that they might finally look into what's wrong with my body. I hate that, had I had depression, they wouldn't have helped me any more and would have dismissed me just as much. I hate that the psychologisation of ME, makes it so I had to minimise my pre-existing mental illnesses, as well as my reactive depression due to medical injustice. As always, it is a pleasure to read you. Thank you so much for sharing your insights with us, your work is really precious!

ReplyDeleteThank you so much for your comment! The experiences you describe are exactly the kind of thing I was trying to account for; the way that ME is psychologised throws us into a complicated knot of related issues that we can't ever address all at once, and I think that's part of the strategy---with a simple trick on their part, we're somehow cast as unreliable, bigoted, and not truly sick, either physically or mentally when that also occurs! Argh!

DeleteBrilliant! There's also the removal of epistemological agency that is present in many mental and physical healthcare situations for "crazy" people, people with contoversialised illnesses, and many marginalised people with legitimised physical illnesses (women, poor people, people from racial minorities, disabled people, LGBTQIA* people, immigrants, working class people, etc.)

ReplyDeleteOur knowledge of both the biomedical/scientific body of knowledge about our conditions and our own experiences, symptoms, experiences and thoughts about those conditions is often ignored, discounted, treated as laughable, aggressive, "not possible", or as us lying or malingering. We lose our agency as human beings.

I have rarely felt more anger and despair than when I was diagnosed with a serious mental illness. I disagreed (for multiple reasons) and calmly explained why. I was ignored and told that people with the dx never wanted to accept it. Asked for a 2nd opinion. This was given without ever meeting or speaking to me, on the basis of my notes, largely those written by the person who misdiagnosed me. I was also taken off all my meds, abruptly (dangerous!). I complained. My meds were reinstated, but I was told that people with this diagnosis complain for malicious reasons, so it was ignored. What?

I was then threatened with loss of any future care in the system unless I went into the Service for that diagnosis.

I was gaslighted, ignored, and had wild assumptions made about me for years in both mental and physical health services as a result, for years. They even assumed I was lying about my education (I was not). My Mental Health notes are about somebody else, who I've never met. My increasingly psychologised chronic physical health problem (chronic pain) isoften denied because "Well, she has Diagnosis, you know".

Also, as a poor, disabled immigrant woman who is too disabled to work, is queer, a socialist and probably neurodivergent, I was already at a disadvantage, but from then on these were taken to be pathological things, not just who I am.

Argh!

I love your blog. Disability solidarity! I hope the advent of Long Covid brings help and a change in attitude towards all of us!

I'm so, so sorry you've been put through all this. It really is a vicious circle, once we have certain diagnoses on our charts, whether they are certain psych diagnoses or para-psych diagnoses like ME (according to psychologisers), all our symptoms can only ever be signs that we are actually unreliable, hysterical, etc. Solidarity back to you---I really hope you find a way to get competent healthcare soon!

DeleteAlso, have you read Dr Jay Watts on Borderline Personality Disorder?

ReplyDeleteReally great article! Thank you for writing.

ReplyDeleteJust wanted to point out a small spelling error (easily fixeable):

“to the point where they are terminal, before doctors cease to psychologist them. “

I’m 99% sure psychologist should be psychologise here (or psychologize).

Merci encore pour l’article intéressant,

Yann

Thank you so much :) It's changed!

Delete