Debates on the Nature of Disease

One of the central debates in the field of philosophy of medicine concerns the

nature of disease. There are many different positions with interesting and

subtle differences, but they are usually divided into two types:

naturalist views which separate disease from health on the basis of

purely natural, biological facts, and normativist views, which

distinguish disease from health at least partly by appeal to value, of

what is good and what is bad for the person involved.

The paradigm naturalist view is that of Christopher Boorse (1977). According

to him, what makes a body diseased is that it is not functioning properly, as

compared against bodies of the same age and sex. So, for instance, a person

with tuberculosis is diseased, in virtue of the fact that their lungs are no

longer able to perform their proper function, as measured by, for instance,

reduced oxygen extraction compared to the average person.

And the most prominent normativist view is that of Rachel Cooper (2002).

According to her, a bodily state is one of disease when it is bad for the

person in that bodily state, that person is unlucky to be in that bodily

state, and ameliorations to this state of affairs can at least in principle be

hoped for from medicine. So what makes the person with tuberculosis diseased,

according to her, is that their pulmonary state is not good for them, that

they are unlucky to be in this state, and that medical intervention might

help.

As is commonplace in analytic philosophy, much of the debate consists in the

presentation of counterexamples (“but an unwanted pregnancy is a bodily state

that isn’t good for one, that one is unlucky to be in, and that might be

remedied by medical intervention—yet it’s not a disease!”) and modifications

to the various theories in response, the refutation of claims made about one’s

theories (for instance, Elselijn Kingma 2007 shows that the appeal to proper

function and comparisons to a statistical norm are both value-laden, such that

Boorse’s view doesn’t count as thoroughly naturalist in the sense of being

strictly biological and therefore value-free), and refinements of coarse

distinctions (thus Alex Broadbent 2019 distinguishes between something being

value-free and something being objective, in the sense of

perspective-invariant: the same from all points of view—as he remarks, these

are independent and conflated in the debate). That is, much of the discussion

takes the parameters of the debate for granted and digs in, so to speak.

What interests me here is why this debate is had at all. Not what conscious or

unconscious drives propel people to engage in this debate, but what is at

stake in the question of what makes a bodily state healthy or diseased.

In a recent paper, Harriet Fagerberg shows that, contrary to what many in this

debate conceive of themselves as doing, they are not engaged in conceptual

analysis. Conceptual analysis is the task of coming to understand what we mean

when we apply various concepts, here, the concept of disease. She argues that

people engaged in this debate do not seem particularly interested in how words

like “disease” are actually used, and indeed use various words quite

interchangeably (“disease”, “disorder”, “illness”, “malady”), and she

concludes that despite their own claims, what is at stake here is not the

linguistic question of how people apply concepts. Rather, she suggests, it is

the metaphysical question of what kind of thing disease is, what cluster of

real properties diseases have in common.

But the participants of the debates do not claim merely to be doing conceptual

analysis. In fact, both Boorse and Cooper begin their famous papers by

remarking on the political stakes of the debate. Thus Boorse writes:

On our view disease judgments are value-neutral, which is our second main result [after the differentiation between theoretical health, absence of disease, and practical health]. If diseases are deviations from the species biological design, their recognition is a matter of natural science, not evaluative decision. (Boorse 1977: 542–3)

He considers it a “main result”, that his theory settles the source of

diseases’s “recognition” as natural science. In a similar vein, Cooper begins

her paper by talking of its political implications:

Whether a condition is considered a disease often has social, economic and ethical implications. Are psychopaths evil or sick? Should the NHS pay for the treatment of nicotine addiction? Is it right for shy people to take character-altering drugs? All these debates may be seen to depend on whether the conditionsare diseases, and developing an account of disease may be hoped to help us in addressing such questions. (Cooper 2002: 263)

Now, neither Boorse nor Cooper develop this political thread any further.

Instead, they immediately retreat to the seemingly apolitical realm of what

Cooper calls “philosophical work” (263): Boorse announces that his “goal in

this paper is to analyze health and disease as understood by traditional

physiological medicine” (542) and Cooper presents hers as “attempt[ing] to

clarify notions of disease” (263). And this seemingly apolitical realm is

where they remain until the end; hence Fagerberg’s sense that they both take

themselves to be concerned with linguistic questions.

But their initial

suggestion that it is political reasons that drive not just the development of

their individual views but indeed the very frame of the debate strikes me as

lucid. What is at stake in the naturalism/normativism debate about the nature

of disease is, I think, the political question of who gets help, who gets

support, who gets funds, who gets compassion; and not just that but who and

what decides it. It is a hallmark of the pragmatist tradition, broadly

construed, to consider that the stakes of things are contained in their use.

And what use does it have, exactly, to distinguish disease from non-disease?

In the case of specific diseases, the answer is clear. Distinguishing

tuberculosis from non-tuberculosis serves to determine a course of action:

which kind of infection control measures to take, which treatments to begin,

which variables to keep under surveillance, how to evaluate the risks to one’s

survival, how to relate to various aspects of one’s life, and so on.

But what

use might lumping all diseases together have? Dealing with illness requires

resources. The costs can be enormous and wide-ranging: the cost of medical

care (including doctors’ fees, medications, fees associated with dispensing

treatment like infusions, injections, etc.), of paramedical care (physical and

psychological therapy, assistance with activities of daily living, costs of

specialised nutrition and food supplements, all sorts of specialised

equipment), and of partial or complete reduction in work capacity, from the

symptoms themselves, and/or from the gigantic administrative and

organisational load of living with a disease. The question arises of who

supplies these resources: of who incurs these costs. And contained within our

concept of disease, as Cooper acknowledges in the citation above, is the idea

you are entitled to these resources if you are sick. If you are sick, you

should (in some sense of should) get medical treatment, assistance with tasks,

a pension to replace lost wages. What is at stake in the question of whether

someone’s bodily state is one of disease or not, is whether or not this person

is entitled to this support.

We should understand the disease debate then, not

as an apolitical metaphysical question, but as an epistemic question (that, in Boorse’s words, of the “recognition” of disease) embedded in a

political context which has major material consequences for people’s lives.

Indeed, in the background of this debate on the nature of disease, we find a

very real sorting process, performed by state and private (healthcare and

insurance) institutions working in tandem. People come in contact with these

institutions, and they are sorted into sick and not-sick, and treated

(or not) accordingly. This sorting process, it bears remarking, has

consequences beyond the economic realm: whether people are classified as

sick by these institutions often has a significant impact not only on

their self-conception, but also on the way they are conceived of and therefore

acted with by kith and kin. It has profound and wide-ranging ramifications for

people’s lives, including for their survival.

Even though, as far as I’m

aware, none of the participants in the debate on the nature of disease

reference this sorting process, any perspicuous reader aware of the political

discourse around illness and disability can recognise it as informing the

various views defended in the debate: discussions arise again and again of

whether this or that account would rule this as a disease, where this is

something widely taken to be something for which a person should receive no

support. Moreover, regardless of the authors’ intentions, discussions of

whether people who claim to be sick really are sick appear chiefly in and

saturate the political, medical, and popular discourse around accommodations,

financial support, and the availability of medical care. Whether they intend

to or not, participants in the debate of what distinguishes disease from

non-disease speak to the question of who should get the support only sick

people are thought to deserve.

According to Boorse, bodily states should be

sorted into ones of disease and ones of non-disease by whether there is

biological dysfunction. This suggests that a task of sorting people into

“really sick” and “not actually sick” should proceed by examining whether

biological dysfunction can be identified. This is roughly the status quo. In

order to be recognised as sick and therefore eligible for whatever meagre

supports are made available by the state and insurance companies, one has to

go through an extensive, invasive, exhausting, and dehumanising process of

demonstrating biological dysfunction considered significant enough by the

institutions in question to warrant said support.

A significant issue with

this process is that biomedical knowledge is at best incomplete, such that

there likely are dysfunctions that cannot currently be detected by the best

available science, that is, diseases by the naturalist’s own lights that would

be wrongly classed as non-diseases—like epilepsy was before the EEG, or

multiple sclerosis before the MRI. (It should be remarked here that many if

not most illnesses branded “medically unexplained” by institutions eager to

deny people benefits are not at all unexplained in the sense that biological

dysfunctions cannot be detected. In myalgic encephalomyelitis for instance,

the illness from which I suffer, significant immune, metabolic, and vascular

dysfunctions are well-documented.)

Cooper’s normativist account fares better

in this regard. According to her, the sick (those then who should receive

support) are those whose bodily state is bad for them. Thus the question of

whether a biological dysfunction can be detected does not arise. She explains

that whether one’s bodily state is bad for one isn’t always known by oneself:

one might for instance have a so-far asymptomatic illness that will go on to

cause suffering or shorten one’s life. One can then learn through biomedical

exploration that one is sick. But one can also know that one is sick if for

instance, one lives with chronic physical suffering. Thus determining whether

someone is sick may but need not involve biomedical investigation: sometimes,

a person’s testimony may be enough.

A sorting process predicated on this kind

of account of disease would avoid the significant difficulties of the

naturalism-based account concerning people whose ills are not easily

detectable by current means of biomedical investigation. But critics will

object that a process that allows self-reporting opens the door for false

reports; indeed Cooper herself raises this possibility:

Sick people may both be stigmatised and receive certain social benefits. Thus people are often motivated to either consciously lie or to deceive themselves regarding whether or not they are sick. (2002: 273)

The political dimension of the debate on the

nature of disease should be evident now: we have made our way to the

widespread inflammatory rhetoric that depicts sick and disabled people as potential liars, fakers, and malingerers, not actually sick as certifiable by a doctor

but pretending for supposed gains. This is the kind of rhetoric employed by

right-wing governments across the world to justify ever increasing

restrictions on life-sustaining and life-improving support for disabled

people, including misery payments on which people cannot survive, and are

forced instead to depend on mutual aid, personal wealth, or die.

The debate

between the naturalist and the normativist accounts of disease ultimately

boils down to a difference of political orientation. On the one hand, we have

a view that insists on what Ellen Samuels calls biocertification: “the massive

proliferation of state-issued documents purporting to authenticate a person’s

biological membership in a regulated group” (2014: 9). On the other, we have a

view that allows for some autonomy, agency, and self-knowledge on the part of

people with recalcitrant bodies.

But both views are formulated within a

particular frame: that outlined above of the public/private assortment of

institutions that decides who gets support. To some, this will be appealing: a

set of institution exists to fulfil the needs of the population, by providing

care to those who need it—the question arises then of who they are. To others

however, myself included, it will fall significantly short of what we dream of

and struggle for: a world where care is no longer rationed and distributed by

the state, but communised and abundant, the collective work and project of us

all. In the world we try to bring into existence, the question of who is sick

and who isn’t doesn’t arise in the same way, because care isn’t predicated on

need, given to some and withheld from others, such that there remains a reason

to determine whether someone e.g. has tuberculosis, since the care we will

want to give them will depend sensitively on that, but not whether someone is

sick as opposed to non-sick, since care will be shared to all.

Now, where does

all this leave us, as far as naturalism is concerned? We have seen that

attempts to appeal to naturalist views within the debate on the nature of

disease amount to accusations of malingering in disguise. Yet the same people,

myself included, who categorically reject these views in that context, are

thorough naturalists about their illnesses. This is because, for us,

naturalism is not a debate to be had, to be opposed to normativism, to be

weaponised in service of biocertification and the attendant abandonment of

sick people. No, naturalism is assumed, it is a framework within which we

think, because it is the only framework within which it is fruitful to think

of illness, when the question isn’t whether we deserve life-sustaining and

life-improving support (a question we do not ask ourselves, but is only ever

imposed on us), but how do we get better.

——

NB. Outlines of others’ views are

written from memory and old informal notes, and with significantly reduced

cognitive function. Please excuse and point out any errors.

References

Broadbent, A. (2019) Health as a Secondary Property. British Journal for the

Philosophy of Science, 70: 609–627.

Boorse, C. (1977) Health as a Theoretical

Concept. Philosophy of Science, 44: 542–573.

Cooper, R. (2002) Disease.

Studies in the History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences,

33: 263–282.

Fagerberg, H. (2023) What We Argue about when We Argue about

Disease. Philosophy of Medicine, 4(1): 1–20.

Kingma, E. (2007) What Is it to

Be Healthy? Analysis, 67(2): 128–133.

Samuels, E. (2014) Fantasies of

Identification: Disability, Gender, Race. New York University Press.

Hi Chloe,

ReplyDeletethanks for the eye opening posts! I had one thought while reading the text - probably not very sophisticated. What I was thinking is that even though I am personally inclined to embrace the naturalist position, I was thinking about the following case: imagine that our level of technological development is such that it does not allow for observing certain diseases. What do we do in such a case? What are these hypothetical patients to rely on? A sociopolitical culture that respects individuals as epistemic agents with regard to how they experience their bodily existence? And if yes, then would this have any entailments for the move to assume naturalism?

Hi Ervin! Thank you for your question. I think that’s not a hypothetical case: there is much that is unknown in biomedical science. So if we *have* to separate people into sick and not, we shouldn’t do that on the basis of whether we can find any biological dysfunction. But towards the end of the post I argue that this sorting process is an artefact of our political economy—the state needs to sort people into those to be forced into work and those to be kept in misery (people who get disability benefits are usually not allowed to even be gifted more than misery amounts: life on disability benefits is a life of abject poverty). And along with a change away from this capitalist political economy, the sorting process would disappear. If care is communised, abundant, and given by all to all, there is no need to determine who is sick as opposed to non-sick.

DeleteVery nice, Chloé, to see that you are "back", at least online. What would you take the implications to be for university or faculty policy concerning paper extension, special examination conditions, etc. for students with illnesses? This was a topic of a recent staff meeting where it was suggested that there was the need to determine who is sick and who is not in order to decide who should (not) get special treatment and what kind of special treatment. Put differently, following on your last line in your reply to Ervin, is there really no more need to determine who is sick and who is not if care is abundant? What should our faculty/university policy be? Getting rid of deadlines might be a good start... ;)

ReplyDeleteHi Marc! Thank you so much for bringing up this question—I hadn’t thought of biocertification in not-obviously-economical contexts. It’s actually a really interesting question and I’ll think about it more, perhaps do a whole post on it. What I’ll say for now is that, if the goal of university education was just to train students to do philosophical research, outside of the economic contexts of certification-for-jobs and academia, and if the resources weren’t limited, there’d be no need to classify students into really-sick and not-actually-sick. The way we’d train each of them would depend on the highly individual question of what’s best for them. So the question of who is *really* sick only arises in a context where resources are scarce (we can’t indidivualise education), and where part of our job—even though that’s rarely made explicit—is to certify students for the non-academic job market (that means, certify that they can perform according to the ableist norms of the market).

DeleteThanks Daphne :)

ReplyDeleteHi Chloé,

ReplyDeletegreat to hear from you, but so sorry that you are still mostly bed bound! I think it is great that you take this opportunity to share your thoughts with the world in a blog format, and the topic of the nature of disease is very interesting and complex - so perfect for philosophical analysis :)

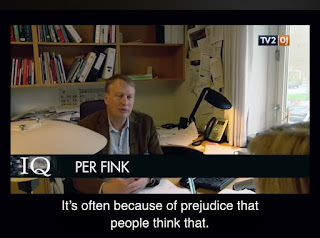

What I understand from my spouse, who is a neurologist, is that the distinction between 'objective' (biological malfunction) and 'subjective' (experienced malfunction) disease is relatively unclear. In particular, there is a class of diseases that are called 'functional disorders' that seem to lie somewhere on the boundary and that are currently ill-understood (although she mentions there is a growing interest in both research and practice for this class of diseases). Given the topic of your current writings, it might be interesting to look into these. They may serve as a useful contact point between philosophical and medical thinking on this topic.

Hi Job! Yes, until a treatment is found and approved for ME, I will unfortunately remain fully bedbound, and it could be years or decades. It’s a very bleak place to be in.

DeleteThe notion of “functional” disorders is not unproblematic, and I plan to write a post about it at some point. The idea is that these are disorders of signalling, rather than disorders of the body itself. But this is an incoherent distinction because signalling is an organic process just like any other.

In practice, diseases including ME are called functional as a polite way of stating they aren’t real, supposedly because biological abnormalities haven’t been documented. Except they have. (I should make clear I’m not talking here of FND, a disease characterised clinically by transient paralysis and loss of motor control, but about supposedly functional illnesses like ME, IBS, etc.)

The growing interest that your partner mentions is unfortunately not welcome by most people with illnesses dismissed as “functional” when they are not. This often leads to very poor quality research that ignores the actual research people have done on the topic, all with the aim of promoting CBT or physical therapy when these not only don’t work but can actually cause harm to patients. It’s a major political stake for us to resist this bad (and sometimes fraudulent) science that usually serves the interests of funding agencies and insurance companies over ours—if our illnesses don’t have a biological basis, we don’t need research, real treatments, and disability benefits, but a vigorous kick to get exercising again and change our “unhelpful thoughts”

(Sorry I pressed send before finishing the comment or adding my name!)

DeleteIf your partner is interested in this class of diseases, I really strongly recommends that she reads about their history and politics, and that she keep a watchful eye for bad science! There’s more to it than meets the eye, if one is just approaching the topic from a patient-detached perspective :)